How Big Law Firms Work

The business of corporate law firms: how they're structured, how they make money and how they beat the competition.

Contents

If you’ve ever wondered how large law firms really work, then this guide is for you.

But first, a note on nomenclature.

This guide looks at the typical structure and operations of a large corporate law firm in the UK.

Broadly, those law firms sitting in the top 25 in terms of revenue, including the likes of the Magic Circle and Silver Circle firms.

To dig a little deeper, we have comprehensive profiles on many of the UK’s top law firms (written by current and former City lawyers). You can check those out here.

Big Law is the term used in the US - and increasingly in the UK, taking precedence over the more traditional City law label (originating from the biggest firms largely being based in the City of London - London’s historic financial district - also known as the ‘Square Mile’).

So, this guide looks at the typical structure of a Big Law firm in the UK.

These firms are all described as corporate law firms - they advise companies, financial institutions, investment firms, governments and other public bodies, rather than individuals (although a small handful do also count high net worth individuals as clients).

Some use the term commercial to describe them i.e. they are all commercial law firms. This works fine too.

Confusingly, these firms all also have large corporate law practices. But this will make up just one of the many practice areas they specialise in.

In that context, we are talking about that firm’s dedicated corporate law practice which advises on matters like M&A, takeovers and corporate governance.

So they’re all corporate law firms with corporate law practices - as well as many others.

Get the free email for UK lawyers with the legal industry and business stories you need to know about to stay ahead. In your inbox, three times a week.

Why should you care about this guide?

If you’re a practising City lawyer, a trainee solicitor or a young professional looking to break into Big Law, you need to know how large firms work as businesses.

This will help you understand the importance and expectations associated with your role and in that context, what you should prioritise day to day and over the long term to align yourself with the firm’s success.

It will also help you to start thinking more commercially.

Law firms want commercially-savvy lawyers in senior decision-making positions i.e. they want commercially-savvy partners.

Commercially-savvy partners aren’t just great lawyers, they know the business of law firms inside out.

They don’t just work in the business, they work on the business, shaping its strategic direction.

We’ll start by giving a brief overview of how law firms are structured, then we’ll look at the various roles and departments within law firms before exploring how law firms actually make the money that pays your salary.

How law firms are structured

Corporate structure

It’s helpful to kick off by looking at how law firms are structured.

While law firms are generally organised in a traditional hierarchical manner, the corporate structuring that underpins them can be done in several different ways.

Here are the most common:

- Limited Liability Partnership (LLP): How most large law firms are set up today. The firm itself is a separate legal entity in the same way as a limited company is.

That limits the liability of partners in the event the firm becomes insolvent - the LLP is responsible for the debts of the firm (ignoring any personal guarantees given by partners).

Like limited companies, LLPs have to file their annual accounts with Companies House. This means that the finances of pretty much all of the UK's largest law firms are publicly available - just search for the relevant firm on the Companies House website.

- Traditional Partnership: Also known as a ‘general partnership’, this is an unincorporated structure with uncapped liability that was traditionally used by law firms.

Among the top firms today only Slaughter and May - still considered the UK’s most prestigious law firm - continues to use this structure. That means it doesn’t have to publish public firm-wide accounts. So revenue and profit numbers are best estimates made by the industry.

- Limited Company: The Legal Services Act back in 2007 allowed non-lawyers to take ownership interests in law firms. That saw several firms shift to a limited company model with a view to taking on external investment.

Mid-sized firms such as DWF, Knights and Gateley are examples of law firms that took this route and decided to list on the stock market to varying degrees of success.

- Swiss Verein (Swiss ver-ein): This structure is used by several international law firms that have come about through mergers, like DLA Piper and Norton Rose Fulbright.

Unlike a full merger where all assets and liabilities and ultimately profits are consolidated at the top of the structure, a verein system allows firms to merge together under one brand while maintaining separate pools of assets and liabilities (think of it as a partnership structure for law firms as opposed to the individual partners).

Firms take this approach as it saves them having to spend time negotiating how to redistribute equity among the new partnership to reflect the very different levels of revenue and profits per partner generated across the different offices.

Practice Areas

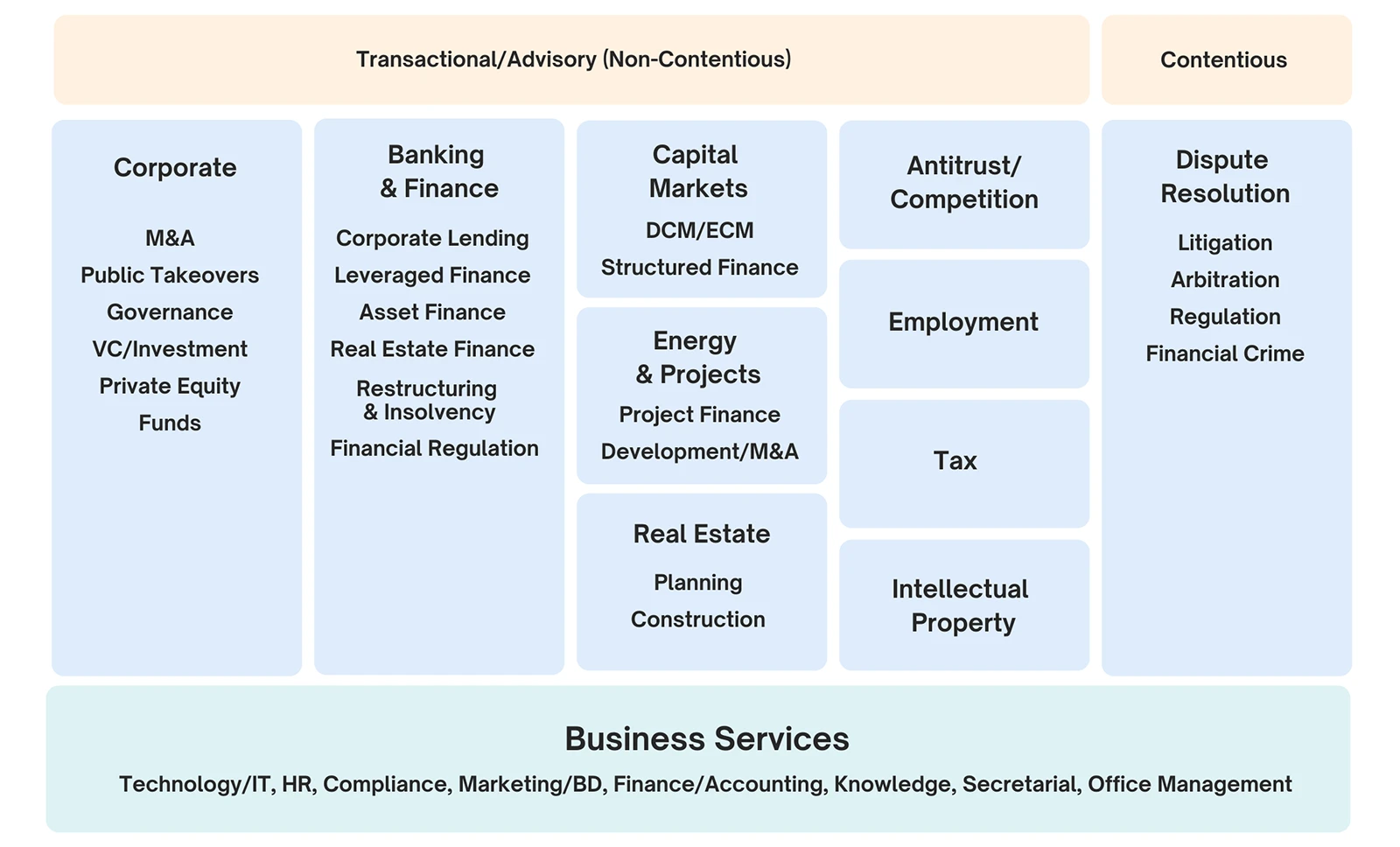

Law firms organise themselves by practice area: various groups of lawyers specialising in particular areas of law. Departments largely mirror these.

Lawyers will generally be sub-divided further within each practice area depending on the degree of specialisation existing within that area.

For example, the M&A team will operate separately from the funds team within the corporate department, and the debt capital markets (DCM) team will operate separately from the structured finance team in the capital markets department.

There will naturally be some overlap between the two areas but the know-how and skillset required will be different, the matters themselves will be different and very often the clients will be too.

Law Firm | Trainee First Year | Trainee Second Year | Newly Qualified (NQ) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Addleshaw Goddard | £52,000 | £56,000 | £100,000 |

| Akin Gump | £60,000 | £65,000 | £174,418 |

| A&O Shearman | £56,000 | £61,000 | £150,000 |

| Ashurst | £57,000 | £62,000 | £140,000 |

| Baker McKenzie | £56,000 | £61,000 | £140,000 |

| Bird & Bird | £47,000 | £52,000 | £102,000 |

| Bristows | £46,000 | £50,000 | £88,000 |

| Bryan Cave Leighton Paisner | £50,000 | £55,000 | £115,000 |

| Burges Salmon | £47,000 | £49,000 | £72,000 |

| Charles Russell Speechlys | £50,000 | £53,000 | £88,000 |

| Cleary Gottlieb Steen & Hamilton | £57,500 | £62,500 | £164,500 |

| Clifford Chance | £56,000 | £61,000 | £150,000 |

| Clyde & Co | £47,000 | £49,500 | £85,000 |

| CMS | £50,000 | £55,000 | £120,000 |

| Cooley | £55,000 | £60,000 | £157,000 |

| Davis Polk | £65,000 | £70,000 | £170,000 |

| Debevoise | £55,000 | £60,000 | £173,000 |

| Dechert | £55,000 | £61,000 | £165,000 |

| Dentons | £50,000 | £54,000 | £100,000 |

| DLA Piper | £52,000 | £57,000 | £130,000 |

| Eversheds Sutherland | £46,000 | £50,000 | £110,000 |

| Farrer & Co | £47,000 | £49,000 | £88,000 |

| Fieldfisher | £48,500 | £52,000 | £95,000 |

| Freshfields | £56,000 | £61,000 | £150,000 |

| Fried Frank | £55,000 | £60,000 | £175,000 |

| Gibson Dunn | £60,000 | £65,000 | £180,000 |

| Goodwin Procter | £55,000 | £60,000 | £175,000 |

| Gowling WLG | £48,500 | £53,500 | £98,000 |

| Herbert Smith Freehills Kramer | £56,000 | £61,000 | £145,000 |

| HFW | £50,000 | £54,000 | £103,500 |

| Hill Dickinson | £43,000 | £45,000 | £80,000 |

| Hogan Lovells | £56,000 | £61,000 | £140,000 |

| Irwin Mitchell | £43,000 | £45,000 | £76,000 |

| Jones Day | £56,000 | £65,000 | £160,000 |

| K&L Gates | £50,000 | £55,000 | £115,000 |

| Kennedys | £43,000 | £46,000 | £85,000 |

| King & Spalding | £55,000 | £60,000 | £165,000 |

| Kirkland & Ellis | £60,000 | £65,000 | £174,418 |

| Latham & Watkins | £60,000 | £65,000 | £174,418 |

| Linklaters | £56,000 | £61,000 | £150,000 |

| Macfarlanes | £56,000 | £61,000 | £140,000 |

| Mayer Brown | £55,000 | £60,000 | £135,000 |

| McDermott Will & Emery | £65,000 | £70,000 | £174,418 |

| Milbank | £65,000 | £70,000 | £174,418 |

| Mills & Reeve | £45,000 | £47,000 | £82,000 |

| Mischon de Reya | £47,500 | £52,500 | £95,000 |

| Norton Rose Fulbright | £50,000 | £55,000 | £135,000 |

| Orrick | £55,000 | £60,000 | £160,000 |

| Osborne Clarke | £54,500 | £56,000 | £94,000 |

| Paul Hastings | £60,000 | £68,000 | £173,000 |

| Paul Weiss | £55,000 | £60,000 | £180,000 |

| Penningtons Manches Cooper | £48,000 | £50,000 | £83,000 |

| Pinsent Masons | £49,500 | £54,000 | £105,000 |

| Quinn Emanuel | n/a | n/a | £180,000 |

| Reed Smith | £50,000 | £55,000 | £125,000 |

| Ropes & Gray | £60,000 | £65,000 | £165,000 |

| RPC | £46,000 | £50,000 | £90,000 |

| Shoosmiths | £43,000 | £45,000 | £97,000 |

| Sidley Austin | £60,000 | £65,000 | £175,000 |

| Simmons & Simmons | £52,000 | £57,000 | £120,000 |

| Skadden | £58,000 | £63,000 | £173,000 |

| Slaughter and May | £56,000 | £61,000 | £150,000 |

| Squire Patton Boggs | £47,000 | £50,000 | £110,000 |

| Stephenson Harwood | £50,000 | £55,000 | £100,000 |

| Sullivan & Cromwell | £65,000 | £70,000 | £174,418 |

| Taylor Wessing | £50,000 | £55,000 | £115,000 |

| TLT | £44,000 | £47,500 | £85,000 |

| Travers Smith | £54,000 | £59,000 | £120,000 |

| Trowers & Hamlins | £45,000 | £49,000 | £80,000 |

| Vinson & Elkins | £60,000 | £65,000 | £173,077 |

| Watson Farley & Williams | £50,000 | £55,000 | £102,000 |

| Weightmans | £34,000 | £36,000 | £70,000 |

| Weil Gotshal & Manges | £60,000 | £65,000 | £170,000 |

| White & Case | £62,000 | £67,000 | £175,000 |

| Willkie Farr & Gallagher | £60,000 | £65,000 | £170,000 |

| Withers | £47,000 | £52,000 | £95,000 |

| Womble Bond Dickinson | £43,000 | £45,000 | £80,000 |

Rank | Law Firm | Revenue | Profit per Equity Partner (PEP) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | DLA Piper* | £3,010,000,000 | £2,400,000 |

| 2 | Clifford Chance | £2,300,000,000 | £2,040,000 |

| 3 | A&O Shearman | £2,200,000,000 | £2,200,000 |

| 4 | Hogan Lovells | £2,150,000,000 | £2,200,000 |

| 5 | Freshfields | £2,120,000,000 | Not disclosed |

| 6 | Linklaters | £2,100,000,000 | £1,900,000 |

| 7 | Norton Rose Fulbright* | £1,800,000,000 | £1,100,000 |

| 8 | CMS** | £1,620,000,000 | Not disclosed |

| 9 | Herbert Smith Freehills | £1,300,000,000 | £1,300,000 |

| 10 | Ashurst | £961,000,000 | £1,300,000 |

| 11 | Clyde & Co | £844,000,000 | £739,000 |

| 12 | Eversheds Sutherland | £749,000,000 | £1,300,000 |

| 13 | BCLP* | £661,000,000 | £748,000 |

| 14 | Pinsent Masons | £649,000,000 | £793,000 |

| 15 | Slaughter and May*** | £625,000,000 | Not disclosed |

| 16 | Simmons & Simmons | £574,000,000 | £1,076,000 |

| 17 | Bird & Bird** | £545,000,000 | £696,000 |

| 18 | Addleshaw Goddard | £495,000,000 | Not disclosed |

| 19 | Taylor Wessing | £480,000,000 | £915,000*** |

| 20 | Osborne Clarke** | £456,000,000 | £771,000 |

| 21 | Womble Bond Dickinson | £448,000,000 | £556,000 |

| 22 | DWF | £435,000,000 | Not disclosed |

| 23 | Fieldfisher | £407,000,000 | £966,000 |

| 24 | Kennedys | £384,000,000 | Not disclosed |

| 25 | DAC Beachcroft | £325,000,000 | £700,000 |

What do City lawyers actually do each day?

For a closer look at the day-to-day of some of the most common types of lawyers working in corporate law firms, explore our lawyer job profiles:

Big Law firms are all known as full service - they offer advice across a wide range of practice areas.

The value add for a full service law firm is that it can offer interdisciplinary (cross-practice) advice to its clients to function like a ‘one-stop shop’.

That way, clients shouldn’t need to appoint scores of different law firms each advising on their particular area of expertise.

For example, an M&A deal will very likely require input from the corporate, banking, tax, employment and real estate teams.

A dispute involving technology might involve the litigation, intellectual property, and data privacy teams.

The diagram above shows the typical structure of a large law firm in the UK - the high level practice areas and the sub-teams within each.

There is an overarching distinction between the type of work that lawyers in corporate law firms work on which you can see across the top of the diagram.

That is, contentious vs non-contentious work:

- Contentious work relates to disputes or potential disputes between parties, often resolved through negotiation, arbitration, or litigation. It’s almost exclusively the preserve of the dispute resolution department in a law firm.

- Non-contentious work involves transactions ('deals'), advisory services, and compliance matters where there is no active dispute. This is what most lawyers in a Big Law firm do (many fewer lawyers than you might think will have much experience of a court room).

The people in a law firm

Now let’s move on and take a look at the people working in a law firm (the most important asset of any professional services business).

Typically, the human elements of the organisation are divided between fee-earners and support staff (or ‘business services’).

Fee-earners

Partners

The senior lawyers who own the firm and who are ultimately responsible for bringing in deal flow, maintaining client relationships and managing the business.

Partners are usually equity or non-equity, with equity partners entitled to a share of the firm’s profits.

- Non-equity partners: In larger firms, new partners tend to start as non-equity partners.

Traditionally, these were most commonly salaried partners - given the ‘partner’ title but not technically a partner of the firm and paid a salary under an employment contract like any other senior employee.

These days, it’s more common for non-equity partners to be so-called fixed share partners - actual partners of the firm with an entitlement to a fixed amount by way of profit share each year (much like a conventional salary).

- Equity partners: Partners who own part of the firm and take a percentage of the firm’s profits each year according to the number of points they have (essentially equating to ‘equity’). Points are awarded according to the particular partnership model that firm has. More on that below.

Each point will be given a monetary value arrived at by dividing the firm's distributable profit for that year by the total number of points allocated to all equity partners. For example, if a firm has £100 million in distributable profits and 10,000 points allocated among partners, each point would be worth £10,000.

Equity partners have to make a capital contribution to the firm’s coffers when they’re promoted (i.e. an investment in the firm).

Many firms arrange financing with banks for partners to borrow the required amount, often at favourable terms. These loans are repaid over time, often through profit distributions.

Equity partners take their profit share by drawings. These are usually paid monthly based on the firm’s anticipated financial performance then, at the end of the year when the firm’s actual profits are calculated, they get topped-up according to their entitlement.

Senior/Managing Associates

These are the most experienced lawyers who have not yet made partner (and may not want to make partner either) - they typically have around at least 6+ years' post-qualification experience (PQE).

They are the workhorses of any law firm and will be most profitable for the partners as they will be charged out at the highest rates and will be working at close to full utilisation (or quite possibly significantly over their target utilisation levels).

Typically, they manage the day-to-day of a client matter on behalf of the partner and will lead the drafting of the most important documents.

A quick note: as the average time from qualification to partnership has increased over the years law firms have introduced various additional titles or ‘pathways’ over the years, including ‘Counsel’ or ‘Of Counsel’.

Ultimately, these are all senior lawyers who are not yet partners. Depending on your viewpoint you can see these as additional rewards on the journey or extra hurdles to overcome…

Associates

These are the junior lawyers working under partners/senior associates, being anywhere from newly qualified (NQs) to 7 or 8 years’ PQE.

Trainee solicitors

Prospective lawyers in training completing a two-year training contract. Trainees will rotate around the firm during their training contract (typically spending 6 months in 4 different departments or ‘seats’). In each seat, they are managed by a dedicated supervisor responsible for their development.

Support staff

Support staff is basically everyone who isn’t billing their time to the client.

That includes roles like professional support lawyers (PSLs) - the know-how lawyers in the firm who will help fee-earning lawyers on technical points of law - paralegals (although many paralegals do in fact charge their time to the client so it does depend), and other support staff like legal secretaries.

Other business functions

In larger firms, this would also include a host of other business functions that are found in any business including dedicated technology, business development, and HR teams - the leaders of which may also rank highly in the organisation more generally.

Technology: Not that long ago the technology function at a law firm was restricted to a very fast and effective IT support desk i.e. a team of people available on call who could fix issues associated with fee earners’ hardware (laptops, phones, printers) and ensure they were regularly updated.

These days, legal tech is big business and the function has become much more strategic and impactful as it leads the development and integration of legal tech solutions to help meet client demands via streamlined workflows, better billing/cost estimation, AI-led legal analysis, improved client experience and data security.

Business Development (BD): The business development team will support the partners in developing and expanding the firm’s revenue streams.

This can mean anything from developing templates for and co-writing client pitches, supporting with client relationship management, performing big picture market analysis and helping with submissions to the big legal directory providers, like Chambers and the Legal 500, to get the firm the best rankings possible.

Human Resources (HR): People are the most important asset in any law firm.

Fee-earners are the factory machines that are used to generate revenue, and staff costs make up around 50% of the total cost base for a law firm as a general rule of thumb.

The HR department’s remit will cover recruitment, retention (i.e. how to keep fee-earners happy via good salaries, benefits, culture and development opportunities), training and performance management (how employees are measured and evaluated, how they are developed), diversity and inclusion and sensitive areas such as partner compensation, workplace conflicts and redundancies.

How law firms are governed

Typically, each partner in the firm will manage their practice covering both the client relationships and the team of fee earners that work for them.

They’ll do that within the confines of their department which itself will have a practice head responsible for managing that practice area.

Major firm-level decisions are made based on the votes of the equity partners, with some partners having greater leverage based on their share of equity or seniority within the business.

Most day-to-day operational decisions, meanwhile, are made by a management committee or board of the firm.

Typically at the top of the firm will be a senior partner and a managing partner, with the support of the practice heads (e.g. Head of Corporate, Litigation etc).

Senior Partner: This is the most prestigious role in a firm. It is an outward-facing role so the senior partner tends to be one of the most experienced and high profile lawyers - equivalent to a presidential role in politics combined with a chairman in the traditional business sense.

The senior partner will set the ‘vision’ for the firm, be the lead representative of the firm in the wider business and client community, and will sit on the firm’s oversight board and chair partner meetings and remuneration committees holding the ultimate decision-making veto.

Managing Partner: This is the second most important role in the firm and tends to be a more inward facing and operational role in comparison to the senior partner, with responsibility for the overall management and day to day running of the firm - think prime minister combined with a COO (chief operating officer).

If the senior partner sets the vision or the ‘goal’ for the law firm, the managing partner's role is to make that happen. The role is incredibly demanding and most managing partners struggle to keep up with fee-earning/client matters whilst they take this on.

Management Board: Most firms have a board of senior management personnel - similar to a board of directors in a company - responsible for operational decisions and the overall governance of the firm. This will be composed of senior partners and is likely to include independent non-lawyers from the world of business as well.

How partnership works

Becoming a partner

The best senior associates will generally be told whether they’re on the ‘partnership track’ (i.e. they have the potential to make partner).

When the time is right, those senior associates will need to develop and present a business case to the existing partners showing why - with their particular combination of expertise and client relationships - they can bring in (or maintain) a steady stream of business to merit their joining the ranks of partnership.

If the partnership agrees (generally through a vote), then that person gets to join their ranks.

(There’s a whole lot of hard work before that, of course.)

Partnership models

There are a range of different profit-sharing models, and each partnership will have its own nuances but the partnership model of most firms falls somewhere on a sliding scale between lockstep and eat what you kill:

- Lockstep: The most traditional model of partnership which is solely based on seniority - the longer a partner has been in the partnership, the more points they receive and the greater their share of the profits. Partners advance through predefined tiers or 'steps' over time. Each step corresponds to a higher share of the firm's profits.

Pros: A lockstep model is considered to promote transparency, loyalty and a more collegiate culture as partners are not directly competing with each other. This means they should be encouraged to work together to grow the overall revenue base. Supporters argue this model is fair because those who have dedicated the most time to the firm over the years receive the greatest share of the rewards.

Cons: At the extremes, the disconnect between current contribution and reward can lead to scenarios where more senior partners are perceived as being overpaid relative to their performance (though some argue this reflects the hard work they've already put in over the years). Meanwhile, junior 'rainmaker' partners may become frustrated by the slower financial rewards for their efforts and could start eyeing opportunities at other firms.

- Modified lockstep: A blended approach with a combination of lockstep and some merit-based elements. Partners are still awarded points according to their seniority, but they can receive additional points based on their individual performance.

Pros: A modified lockstep model retains the perceived teamwork and stability of a lockstep structure while allowing the firm to offer faster progression to better retain star partners who might otherwise leave for firms with pure performance-based systems. (It also allows the firm to exert more control over under-performing partners.)

Cons: There is always a question over how best to measure individual 'performance' and decisions can appear arbitrary. Common measures might include rewarding partners who bring in new clients with so-called client origination credits, rewarding partners who take on firm management responsibilities, and factoring in the revenue generated by a partner's practice area.

- Merit-based: At the other extreme is the merit-based model aka ‘eat what you kill’ where each partner's slice of the overall profit pie is proportional to the share of revenue they brought in that year. This is very much championed by US heavyweights like Kirkland & Ellis and Paul Weiss.

Pros: An eat-what-you-kill model naturally creates strong incentives for performance with partners highly motivated to bring in clients, generate revenue, and maximise their individual contributions. Pay is is directly linked to measurable outputs, which is supposed to reduce ambiguity and potential disputes over profit allocation. Many would argue it's the fairest - most meritocratic - model of all.

Cons: A highly competitive, not at all collaborative partnership is the big risk of the eat-what-you-kill model. Partners may prioritise their own client matters over the firm's longer-term interests.

As for current trends in Big Law world, it's fair to say that traditional lockstep models among UK firms are being adjusted to incorporate more performance-related elements with variations of the modified lockstep model now preferred.

This is seen as a defensive move against rainmaker-hungry US firms poaching top talent in London.

A&O Shearman adopted a three-tier modified lockstep system in 2024 after its merger with Shearman & Sterling, Clifford Chance has also made changes to its partnership model to better reward star performers, while Linklaters has explored a similar shift.

Ever traditional Slaughter and May remains one of the last true lockstep firms.

How law firms make money

The overall revenue of a law firm is almost exclusively made up of the fees charged to clients.

The billable hour model

Law firms provide legal advice and services to clients under a billable hour model.

Every lawyer in the firm has a charge-out rate - the amount it costs for an hour of their time.

Lawyers record all the time they spend working on client-facing matters, typically tracked down to the nearest six-minute unit.

When they submit their time to the relevant client file it becomes work in progress (WIP) - work that's been performed but not yet billed to the client (WIP is a key financial metric for any law firm).

When a client project has been completed, the partner will invoice the client for the time spent by applying the hourly rate of each fee earner against the time they each recorded on that matter.

How hard each lawyer is working on profit-generating activity is tracked using an important productivity metric - utilisation. How hard a lawyer is working, in other words.

Utilisation is calculated by dividing billable hours worked by the number of working hours available.

For example, if a lawyer billed 20 hours in a week and their firm uses a 40-hour working week (8 hours a day - which is typical) as a benchmark, then their utilisation rate is 50%.

High utilisation indicates that a lawyer is adding value to the firm. They are a profitable asset for the firm - the revenue they generate far exceeds what it costs the firm to pay their salary.

Utilisation is closely linked with target billable hours which in a top firm is typically between 1,400-1,800 hours a year for all fee-earners.

If we break this target down (i.e. 365 days in a year, minus 104 weekend days, 8 bank holidays, and 25 days of annual leave, that leaves 228 working days) this translates into 6-8 billable hours per working day.

That seems perfectly manageable…

But remember, the reality of a working day is that it also involves a lot of admin work - attending internal meetings, keeping up with training and development and other tasks that are still ‘useful’ but not directly billable.

And also the nature of legal work varies by department.

Some transactional lawyers (e.g. M&A lawyers and banking lawyers) can have their timers running all day on busy matters.

Work in other departments is more advisory and patchy - you might be working on six different smaller matters with regular interruptions and only end up with four hours of actual billable time at the end of the day.

So outside of peak activity when you ignore anything else that comes into your inbox (e.g. the week or two leading up to a signing or a completion) it will often take a full 12-hour day in the office to actually hit that 8 billable hours target.

How law firms grow their revenue and boost profits

Law firm partners care about maximising profits. That's how they get paid.

In simple terms profit = revenue minus costs, and the biggest cost for law firms (by far) is people - the lawyers and support staff that supply the legal services to the firm’s clients.

(If you want evidence of this, take a look at our list of salaries paid by all of the UK's top law firms here.)

PEP (profit per equity partner) remains a widely used yardstick for law firm financial performance and is still the most commonly used metric to compare performance across firms.

The higher a firm's PEP, the more prestigious it's considered to be. A high PEP also functions as a powerful magnet to attract equity-hungry talent from competitor firms.

The million-dollar question then: how do you make your legal machine deliver more profit?

Let's have a look at the levers you can pull to increase revenue.

While managing costs is always a priority, increasing revenue is the most significant driver for boosting profits in a law firm.

Hire more lawyers

More lawyers means more billable hours which means more revenue, right? Well, yes but...

Unlike the machines in traditional businesses that can run all day and night, lawyers are in fact people - they also need to do things like commute, eat, rest and sleep.

There is a natural limit on the number of billable hours that any one fee-earner can manage.

Department heads will keep a close eye on their fee-earners’ utilisation rates - if they’re consistently too high (above 100%), they’ll want to avoid them burning-out…

by adding more lawyers to the team to do the work…

but this also increases costs…

so they have to be very sure of their pipeline of work to make sure it’s done profitably.

In summary, there is a natural limit to your legal team’s output which can only be boosted by increasing headcount - but this then increases costs.

Law firms are essentially losing money on fee-earners with consistently low utilisation rates - the revenue they are generating is not enough to cover what it costs the firm to pay them.

Increase charge-out rates

Law firms can hike the hourly rates they charge their fee-earners out at to boost revenue.

(Law firms are good at doing that - the UK’s top 10 law firms are charging clients almost 40% more per hour than they were five years ago, according to PwC's annual law firm survey in 2024.)

But…

There's a natural cap on what can be charged which is guided by the wider market - rates for fee-earners among firms of a similar band will often be remarkably consistent.

And clients want value for money. Partners can’t simply load project teams with their highest priced fee-earners (i.e. partners and senior associates). Clients expect the more basic elements to be dealt with by more junior lawyers, paralegals or even outsourced to low cost teams.

And, further, it’s not always as simple as billing the client what’s on the clock at the end of a project anyway…

As part of managing the relationship with the client, the partner may choose to write off some of the time to reduce the bill or apply a discount on fees (as they also always need to consider client satisfaction - if a client doesn't feel they got value for money, they are unlikely to come back next time).

This will impact the recovery/realisation rate which is another key law firm business metric.

Recovery rates measure the amount actually billed to the client as a percentage of the total billable time recorded on the file.

This is used as a factor to assess whether the partner has priced the matter correctly and how efficiently their team has delivered the work.

And then, even though the firm has done the work and billed it, the firm still needs to actually get paid.

Law firms have notoriously bad cash flow problems because much of their revenue is 'locked up' in unpaid invoices sitting with clients - many of which take months to get paid - while each month they’ve still got huge overheads like their lawyers’ salaries to pay.

Law firm metrics like time to recovery and lockup period lengths are used to track this, and firms will deploy dedicated members of their accounts department to get invoices paid as soon as they can.

There are also a host of alternative fee arrangements that firms use instead of the traditional billable hour model.

Alternative fee arrangements

The most common alternatives include:

- Fixed or flat fees: This is where a service e.g. drafting a contract or reviewing documents is done at a fixed rate or price. Clients prefer fixed fees for the added certainty vs being charged on a standard billable hours basis.

Fixed fees are usually applied to standardised, high frequency low value matters, but advances in legal tech are likely to unlock more accurate billing estimates with this approach applied to more complex/high value projects. - Capped fees: A variation of billable hours where work is billed on an hourly basis up to a pre-agreed maximum.

Typically used for smaller matters with more concrete project scopes or where a firm wants to earn brownie points with a client. Capped fees help clients to budget more accurately like a fixed fee with the advantage that you might end up with a lower final bill than expected. - Contingency or success based fees: Most commonly used in litigation - the firm only gets paid if the client wins their dispute. The payout will be a percentage of the settlement and can represent huge paydays for law firms - far exceeding the billable hour equivalent on the clock.

Win more business

Lateral hires

The other driver of growth and profit is winning more business for the firm of course - winning new clients and winning more work from existing clients.

We’ve said it before and we’ll say it again: people/talent are the key assets of a law firm.

The fastest way for law firms to win new clients is to hire individual partners or entire teams of partners (and their associates) from rival firms that have the relationships with those clients.

It’s not guaranteed, but more often than not a partner that gets poached by another firm will bring their key client relationships with them to their new firm. That’s the whole point.

These types of partner moves are called lateral hires.

The partner is being recruited by another law firm to fill a strategic need - namely to increase that firm’s market share in a particular sector (i.e. its share of the total market for legal advice in that sector) or to enter a new market altogether by expanding the practice areas the firm advises on.

These kinds of moves can literally transform a law firm’s prospects in a particular sector almost overnight.

That’s why large firms are willing to entice rainmaker partners from rivals with huge compensation packages.

That is their equivalent of the up front investment cost in research and development that Apple might make in a new smartphone, for example. It’s then up to that new partner to justify the cost by landing work from the clients they’ve brought with them.

The sector that’s been the best example of this over the last few years is private equity and the big trend has been US firms - like Kirkland & Ellis and Paul Weiss - aggressively expanding their private equity practices in London by poaching top talent from the elite UK firms as well as their US rivals in the City.

Expand internationally

Firms can also choose to open new offices in strategic domestic or international locations to tap into new markets.

Clients operating in multiple jurisdictions often prefer law firms with a global footprint for consistent service delivery across regions. Expanding to new locations allows firms to serve these clients better and win more cross-border work.

Merge with another law firm

The other way for law firms to win more business and grow their market share is through their own equivalent of a lateral hire - merging with another law firm.

We don’t need to get into the details of all the reasons why two law firms might decide to merge, but the overarching objective in most cases is to access new markets - either domestically or internationally.

The biggest example in recent years was Allen & Overy's decision to merge with US firm Shearman and Sterling that went live in 2024, creating A&O Shearman.

The primary driver of that combination was to give London-based firm A&O a stronger foothold in the US market - the world’s biggest and most lucrative market for legal services.

The merger gave it a whole new book of US-based clients and an improved capability to serve their existing base of clients for US-based work.

| Firm | London office since | Known for in London |

|---|---|---|

| Baker McKenzie | 1961 | Finance, capital markets, TMT |

| Davis Polk | 1972 | Leveraged finance, corporate/M&A |

| Gibson Dunn | 1979 | Private equity, arbitration, energy, resources and infrastructure |

| Goodwin | 2008 | Private equity, funds, life sciences |

| Kirkland & Ellis | 1994 | Private equity, funds, restructuring |

| Latham & Watkins | 1990 | Finance, private equity, capital markets |

| Milbank | 1979 | Finance, capital markets, energy, resources and infrastructure |

| Paul Hastings | 1997 | Leveraged finance, structured finance, infrastructure |

| Paul Weiss | 2001 | Private equity, leveraged finance |

| Quinn Emanuel | 2008 | Litigation |

| Sidley Austin | 1974 | Leveraged finance, capital markets, corporate/M&A |

| Simpson Thacher | 1978 | Leveraged finance, private equity, funds |

| Skadden | 1988 | Finance, corporate/M&A, arbitration |

| Weil | 1996 | Restructuring, private equity, leverage finance |

| White & Case | 1971 | Capital markets, arbitration, energy, resources and infrastructure |

| Law firm | Type | First-year salary |

|---|---|---|

| White & Case | US firm | £32,000 |

| Stephenson Harwood | International | £30,000 |

| A&O Shearman | Magic Circle | £28,000 |

| Charles Russell Speechlys | International | £28,000 |

| Freshfields | Magic Circle | £28,000 |

| Herbert Smith Freehills | Silver Circle | £28,000 |

| Hogan Lovells | International | £28,000 |

| Linklaters | Magic Circle | £28,000 |

| Mishcon de Reya | International | £28,000 |

| Norton Rose Fulbright | International | £28,000 |

Wrapping up

So there you have it, we’ve covered a lot of ground here but really this still remains an introduction to the business of law firms.

For lawyers, the key takeaway is to always visualise how you fit into the bigger picture and, most importantly, to grasp the commercial realities behind the legal work you and your colleagues do for clients.

As you deepen your understanding of this, you’ll start to add even more value.

You won’t just be good at doing the work, you’ll be actively contributing to the growth and success of your firm.

Partners will recognise this and they will reward you - trust us.

Law Firm | Trainee First Year | Trainee Second Year | Newly Qualified (NQ) |

|---|---|---|---|

| A&O Shearman | £56,000 | £61,000 | £150,000 |

| Clifford Chance | £56,000 | £61,000 | £150,000 |

| Freshfields Bruckhaus Deringer | £56,000 | £61,000 | £150,000 |

| Linklaters | £56,000 | £61,000 | £150,000 |

| Slaughter and May | £56,000 | £61,000 | £150,000 |

Law Firm | Trainee First Year | Trainee Second Year | Newly Qualified (NQ) |

|---|---|---|---|

| A&O Shearman | £56,000 | £61,000 | £150,000 |

| Clifford Chance | £56,000 | £61,000 | £150,000 |

| Freshfields Bruckhaus Deringer | £56,000 | £61,000 | £150,000 |

| Linklaters | £56,000 | £61,000 | £150,000 |

| Slaughter and May | £56,000 | £61,000 | £150,000 |

Law Firm | Trainee First Year | Trainee Second Year | Newly Qualified (NQ) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ashurst | £57,000 | £62,000 | £140,000 |

| Bryan Cave Leighton Paisner | £50,000 | £55,000 | £115,000 |

| Herbert Smith Freehills | £56,000 | £61,000 | £145,000 |

| Macfarlanes | £56,000 | £61,000 | £140,000 |

| Travers Smith | £54,000 | £59,000 | £120,000 |

| Firm | Merger year | Known for in London |

|---|---|---|

| BCLP | 2018 | Real estate, corporate/M&A, litigation |

| DLA Piper | 2005 | Corporate/M&A, real estate, energy, resources and infrastructure |

| Eversheds Sutherland | 2017 | Corporate/M&A, finance |

| Hogan Lovells | 2011 | Litigation, regulation, finance |

| Mayer Brown | 2002 | Finance, capital markets, real estate |

| Norton Rose Fulbright | 2013 | Energy, resources and infrastructure, insurance, finance |

| Reed Smith | 2007 | Shipping, finance, TMT |

| Squire Patton Boggs | 2011 | Corporate/M&A, pensions, TMT |

Law Firm | Trainee First Year | Trainee Second Year | Newly Qualified (NQ) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ashurst | £57,000 | £62,000 | £140,000 |

| Bryan Cave Leighton Paisner | £50,000 | £55,000 | £115,000 |

| Herbert Smith Freehills Kramer | £56,000 | £61,000 | £145,000 |

| Macfarlanes | £56,000 | £61,000 | £140,000 |

| Travers Smith | £54,000 | £59,000 | £120,000 |

Our newsletter is the best

Get the free email that keeps UK lawyers ahead on the stories that matter.

We send a short summary of the biggest legal industry and business stories you need to know about three times a week. Free to join. Unsubscribe at any time.